From Music to Poetry

Somali rapper Keinan Abdi Warsame, more commonly known by his rap name K’naan, has risen in recent years as one of the most renowned music performers of our time. However, his style on stage can differ greatly from traditional, customary approaches to Rap. From personal experience having the chance to attend a K'naan concert, I have observed his unique style of performance.

Unlike any other rapper I have seen in concert, K’naan punctuates each song or tune with one or two pieces of poetry he has written. Similar approaches of presentation have been attempted in various contexts. For instance, Toni Morrison divides the sections of her novel The Bluest Eye with short excerpts from the children’s book Fun With Dick and Jane that become almost poetic under Morrison's pen, providing an ironically simplistic vignette for the following section of the story. Morrison uses this technique to provide a different way of perceiving the themes of her written work and briefly deflects the reader's attention from the issues discussed in the novel to borrowed variations of the same themes. K’naan and Morrison both use this method of taking some outside source of literature to strengthen the points relating to racial discrimination and social injustice made in their main work. In fact, others have also seen this connection between Morrison’s work and poetry as one critic expresses on the back cover of the novel, “so precise, so faithful to speech and so charged with pain and wonder that the novel becomes poetry” (The New York Times). Interestingly, K'naan's various songs and poetic works include a children’s book that was recently released this September, written by K’naan himself and called When I Get Older: The Story Behind “Wavin’ Flag”, telling the story of his family’s move to New York to escape the daily threat of murder and kidnapping consuming Somalia during the 1990’s.

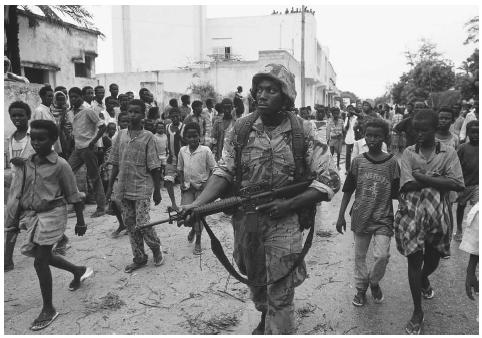

Because he is an immigrant from Somalia to the U.S. and a victim of the severity of the Somali Civil War, K’naan’s music is tightly linked to the concerns presented in areas where oppression and high levels of prejudice are intensely problematic. The song “America” is ironically sung mostly in the Somali language, accentuating an atmosphere of ambiguity between his old and new worlds.

There are certain things fresh and certain things mesh

I got my own sound, I don't sound like the rest

And even my attire and my choice of dress

And not long ago I don't spoke English

My point is police pull me over a lot

They wonder what kind of rap sheet I got

And sometimes I take a young girl out to eat

And hold the door open, oh you're so sweet

Of course my affection's super illustrated

And I like to give, don't reciprocate it

Unless you could give me someone innovated

Well let's cook it up, we don't refrigerate it

But back to the country of the educated

Where people get robbed and they celebrate it

Throughout the song, K’naan flashes his pride in his uniqueness about nearly everything he does: his “choice of dress,” and how he “don’t sound like the rest.” A difficultly for many immigrants coming to the U.S. from non-industrialized countries is a sense that their culture is insignificant or disregarded in the new world. In response, many of these immigrants have given-in to American culture and even attempt to hide indications of foreignness. K’naan presents through his music that the cultural differences between his country and that of America do not have to clash. Instead, they can coexist without imposing upon each other. K’naan’s music pressures and challenges immigrants like these to wear their abnormalities on the outside instead of hiding them on the inside, an idea (of passing as a member of American culture) that has become a staple throughout many immigrant populations.

Aside from the specific topics that K'naan raps about, simply the contrast of languages throughout the song between Mos Def, Chali 2na, and K’naan creates a structure to the song that exemplifies the ideas of coexistent cultures in a single world. While many hide from their cultures, K'naan aligns American culture and his own Somali culture to compare the flaws in each: "back to the country of the educated where people get robbed and they celebrate it." Here, it is noted that Somalia does not allow for most citizens to receive any education due to a lack of organized governmental control while America provides opportunity for all to obtain some degree of education publicly. Yet the next line points out America's tendency to celebrate parts of U.S. history that damaged other cultures and societies in pursuit of American ideals. Many people in America celebrate the settling of the pilgrims in colonial times while others may see it as more of an invasion of land and property, leaving many people native to the areas homeless. In addition to this reference to a conflict hundreds of years ago, K'naan, in the same line, also notes the high crime rate present in the U.S. raising questions of similarities to the excess in violence occurring in Somalia during its civil war.

magaeygu waa sharaf [she says: My name is Sharaf]

sharaf haaji weeyan [Sharaf Haaji, it is]

aqalada hariirta [Those beautiful houses]

dhina baan ka jooga [I live beside]

alla ya u sheega [Somebody please tell them]

tinta u shanleeya [give them a clue]

This verse takes the song in a slightly new direction speaking from the perspective of a young Somali girl who seems to be observing aspects of the world that many would consider unpleasant to discuss. She observes the "beautiful houses," not as an inspiration for her own life and livelihood, but to "live beside," again comparing the cultures of one wealthy nation to less privileged nations such as Somalia. She asks for somebody to expose the wealthy to the hardships endured by people living in underdeveloped countries, revealing the wealthy's reluctance to spare their resources for those in need. "Those beautiful houses" referred to in the verse also draws attention to ideas of the "American Dream." Often presented with imagery of white picket fences and neatly kept lawns, the dream collects ideals from white supremacist views early in U.S. history that has resulted in many Americans low in social class unable to move past a certain point in the societal hierarchy.

Like K'naan, many other performers have attempted to send a message promoting cultural pride. Many characters and famous people, such as Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, during the Harlem Renaissance were extremely involved in the awareness of white supremacist oppression through literary or art works. This sort of rebellion against discrimination followed throughout the 20th century. Other music performers prior to K'naan made many attempts to reach out to immigrant populations in the U.S., bringing their cultures closer together. James Brown's "I'm Black and I'm Proud" is a song that especially focuses on African-American pride and feelings of ownership of their ethnicity.

Morrison addresses the issue in an ironic way by exploring the idea of social self-denial through characters such as Pecola, Geraldine, and Junior in The Bluest Eye. Pecola’s obsession for blue eyes through the end of the novel comes from figures, such as Shirley Temple, advertised as socially acceptable or beautiful. Her desire to become beautiful like the white people presented in Shirley’s films consumes her to the point that she convinces herself that her eye color has changed in a way that is suitable to the culture of socially high-class individuals. Geraldine's desire for social beauty carries her to a level of unfortunate acceptance in which she, instead of trying to make herself more white, tries to make herself less black.

Between black people, "niggers," and white people, Geraldine inserts a new social class, which she teaches to her son, Junior-- that class is referred to as "colored" rather than black (87). The difference she presents to him is that colored people are "neat and quiet" (perhaps also her perception of white people) while niggers are "dirty and loud" (87). To act white is not to be white, but to Geraldine, embracing white culture is the only way to not be a nigger (the lowest social class on the racial hierarchy). Junior also struggles with the conflict between white culture and black culture, not only at home with Geraldine but at "his" playground as well. Junior's hesitance to play with the other black children forces him to realize the differences between the two cultures. From what he can see, black children indeed do get dirty and play loudly while white children seem to not. An inner conflict arises when he questions the authority of white culture and begins to desire playing with the other black children.

While K'naan had poetry in mind when performing on stage, Morrison had music in mind when writing The Bluest Eye:

The pieces of Cholly's life could become coherent only in the head of a musician. Only those who talk their talk through the gold of curved metal, or in the touch of black-and-white rectangles and taut skins and strings echoing from wooden corridors, could give true form to his life... Only a musician would sense, know, even knowing that he knew, that Cholly was free. Dangerously free. Free to feel whatever he felt. (159)

Toni Morrison, here, uses a concept similar to one written by W.E.B. Dubois where the idea of music becomes a sort of code that only certain people can crack. These people are in touch with a kind of musicality performed by "only those who talk their talk." This inner circle being described simply refers to the black community where only African-Americans could understand certain aspects of a black person's mannerisms or thoughts. Music has an emotional tie, specific to a certain group of people who listen to that kind of music. In contrast, plain language has a feeling of practicality, giving it the malleability of universally being understood among any number of people.

During the times of slavery in the U.S., plantation slaves were known for singing in unison with their work to help pass the time and also send coded messages to one another so that the master would not hear or understand. Cholly's case, however is slightly different. To describe Cholly as simply decoding a message would be incorrect. Morrison goes one step further to describe Cholly by expressing that, though other black people see through the coded messages of the music, he can only be seen by the people who see the music. This level of invisibility gives him the "freedom" that no other character in the story ever experiences: the freedom of being hidden.

Artists across all genres, whether in music or literature, have distinguished issues of immigrant cultures when contrasted with American culture and often identify a problem in miscommunications between the two. K'naan's wish through the music he writes is a world where someone foreign to a country does not feel a need to pass as a native member of that society, yet can exhibit their own cultures without criticisms from peer communities. In addition, Toni Morrison uses characters from her novel to make apparent the effects of these criticisms, providing examples of people through fictional personifications of the result of oppressive behavior.

Really solid blog Julian. The way you related how K'naan splits his concerts into sections through poetry with how Toni Morrison divides The Bluest Eye with the Dick and Jane Readers was really interesting. I also liked it when you related K'naan's cultural pride to the racial pride of writers from the Harlem Renaissance such as Langston Hughes and Claude McKay.

ReplyDelete